If you grew up with your grandma or great-grandma making bread in West Virginia, there’s a good chance it was salt rising bread.

Don’t let the name fool you – there’s no salt in this bread. And, there’s no yeast.

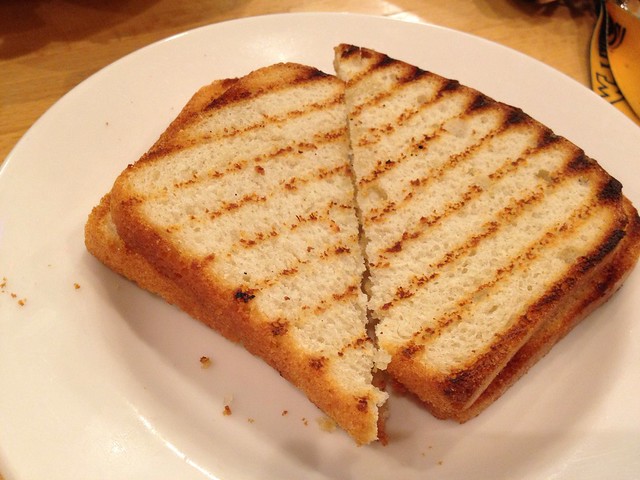

This dense white bread is an Appalachian creation that doesn’t rely on yeast to rise. Yeast, which was likely only found at a brewery in the 18th or 19th century, may have been difficult to come by in rural areas during the early pioneer days. Innovative women likely crafted this recipe out of necessity or happenstance.

Salt rising bread instead relies upon the bacteria in potatoes or cornmeal and flour that goes into the starter in order to rise. The exact science of this bread is a bit shrouded in mystery, but time and temperature are key variables in the process – a lot of both.

As for the name “salt rising bread” – which has little to no salt in the recipe – there are a few theories: that in the early days, women kept the starter dough warm by placing it in the salt barrel on top of the wagon wheel while they traveled, and that was warmed by the sun. Another is that the starter was surrounded by rock salt that was kept warm on the hearth. And, yet another is that it’s an evolution of the word “saleratus,” which was an ingredient used in the early recipes prior to baking soda.

Whatever the origin, it’s a tradition that has been passed down through generations in Appalachia, though very few people continue to make the bread in this authentic way today.

Jenny Bardwell and Susan Brown, authors of Salt Rising Bread: Recipes and Heartfelt Stories of a Nearly Lost Appalachian Tradition, are working to keep the craft alive and document its history.

Bardwell, proprietor of Rising Creek Bakery in Mt. Morris, Pa. which specializes in salt rising bread, and Brown, who is the founded of The Salt Rising Bread Project website, traced salt rising bread’s history and found the earliest recipe they found for “Salt Risen Bread” comes from West Virginia in 1778.

“The pioneer women who discovered that they could ‘raise’ bread dough without yeast may not have understood how it happened, but they seized the moment and repeated the process until they perfected it. And they shared,” the co-authors wrote in their book.

Bardwell and Brown are sharing their knowledge with others through classes at the bakery have taken it upon themselves to be the “chroniclers and preservers” of this nearly lost tradition.

“I’m devoted to this bread because I learned it from my grandmother, and it has been in my family for generations, and it’s a precious tradition that I don’t want to lose,” Brown said. “This is our heritage, and it was made by these Appalachian women who didn’t have another way to make bread so they relied on their ingenuity and resourcefulness, and I think it’s important to keep that spirit alive.”

Brown said so few people make this traditional bread anymore for a few reasons.

“One, it can be tricky and two, it’s very time consuming. It’s a lot of hours to be at home and make sure you’re there to tend to it. And, many women are working full time and aren’t home like they used to be. So, the tradition – which had been handed down through families – is being lost, and that’s why it’s important to keep it alive however we can,” she said.

Those who grew up with the bread long for that cheese-like flavor and fine crumbly texture. Those who aren’t as familiar often scrunch their noses up at the microbial bread’s distinct smell but fall in love at first bite.

This bread is much like our region – steeped in tradition and resourceful. It’s these qualities that help define Appalachia, and paying homage to these traditions helps keep our history alive.

The Appalachian bread is important in our state’s culinary history, and through devotees like Bardwell and Brown, this tradition will not be lost.

SALT RISING BREAD RECIPES

While Bardwell and Brown collected 150-200 salt rising bread recipes, most of them fell into two categories: the cornmeal & flour method or the potato method.

Both of the below recipes are featured in “Salt Rising Bread: Recipes and Heartfelt Stories of a Nearly Lost Appalachian Tradition” and were the ones the authors learned from.

Pearl Haines’s Salt Rising Bread Recipe

Ingredients:

1/2 cup scalded milk

3 teaspoons cornmeal

1 teaspoon flour

1/8 teaspoon baking soda

Preparation:

1. Pour milk onto dry ingredients and stir.

2. Keep warm overnight until foamy.

3. After the raisin’ has foamed and has a rotten cheese smell, in a medium-sized bowl add 2 cups of warm water to mixture, then enough flower (about 1½ cups) to make like a thin pancake batter. Stir and allow to rise again until it becomes foamy. This usually takes about 2 hours.

4. Next, add 1 cup of warm water for each loaf of bread you want to make, up to 6 loaves (e.g., 6 cups of water makes 6 loaves of bread). Add enough flour (20 cups for 6 loaves or about one 5 pound bag of flour plus 1/3 bag of flour). Form into loaves and grease tops. Let loaves rise in greased pans for 1.5 to 3 hours – sometimes longer if it is a cold day.

5. Bake at 350 degrees for 35 to 45 minutes or until loaves sound hollow when tapped.

Katheryn Rippetoe Erwin’s Salt Rising Bread

Ingredients:

1 medium Irish potato, sliced and placed in a jar

ADD: 1 tablespoon cornmeal

¼ teaspoon soda

¼ teaspoon salt

2 cups boiling water

Preparation:

1. Cover and let rise in a warm place until morning. (I set mine on top of the pilot light on my hot water tank). If the mixture is foamy and has the salt rising bread “aroma” the next morning, pour off the liquid and throw away the potatoes.

2. Mix 2 cups of very warm water with ½ cup of shortening. Then add 1 teaspoon salt, 4 teaspoons sugar, and 5 cups flour. Combine with rising mixture (starter) to make a stiff batter. Let this rise until double in bulk.

3. Work in 6 cups of flour, to make a soft dough. Divide into 3 portions. Let rise 10 minutes. Knead for 3 minutes. Place in 3 greased pans. Let rest until dough reaches the top of the pan.

4. Bake at 450 degrees for 15 minutes, then at 400 degrees for 25 minutes.

-->

Don’t let the name fool you – there’s no salt in this bread. And, there’s no yeast.

This dense white bread is an Appalachian creation that doesn’t rely on yeast to rise. Yeast, which was likely only found at a brewery in the 18th or 19th century, may have been difficult to come by in rural areas during the early pioneer days. Innovative women likely crafted this recipe out of necessity or happenstance.

Salt rising bread instead relies upon the bacteria in potatoes or cornmeal and flour that goes into the starter in order to rise. The exact science of this bread is a bit shrouded in mystery, but time and temperature are key variables in the process – a lot of both.

As for the name “salt rising bread” – which has little to no salt in the recipe – there are a few theories: that in the early days, women kept the starter dough warm by placing it in the salt barrel on top of the wagon wheel while they traveled, and that was warmed by the sun. Another is that the starter was surrounded by rock salt that was kept warm on the hearth. And, yet another is that it’s an evolution of the word “saleratus,” which was an ingredient used in the early recipes prior to baking soda.

Whatever the origin, it’s a tradition that has been passed down through generations in Appalachia, though very few people continue to make the bread in this authentic way today.

Jenny Bardwell and Susan Brown, authors of Salt Rising Bread: Recipes and Heartfelt Stories of a Nearly Lost Appalachian Tradition, are working to keep the craft alive and document its history.

Bardwell, proprietor of Rising Creek Bakery in Mt. Morris, Pa. which specializes in salt rising bread, and Brown, who is the founded of The Salt Rising Bread Project website, traced salt rising bread’s history and found the earliest recipe they found for “Salt Risen Bread” comes from West Virginia in 1778.

“The pioneer women who discovered that they could ‘raise’ bread dough without yeast may not have understood how it happened, but they seized the moment and repeated the process until they perfected it. And they shared,” the co-authors wrote in their book.

Bardwell and Brown are sharing their knowledge with others through classes at the bakery have taken it upon themselves to be the “chroniclers and preservers” of this nearly lost tradition.

“I’m devoted to this bread because I learned it from my grandmother, and it has been in my family for generations, and it’s a precious tradition that I don’t want to lose,” Brown said. “This is our heritage, and it was made by these Appalachian women who didn’t have another way to make bread so they relied on their ingenuity and resourcefulness, and I think it’s important to keep that spirit alive.”

Brown said so few people make this traditional bread anymore for a few reasons.

“One, it can be tricky and two, it’s very time consuming. It’s a lot of hours to be at home and make sure you’re there to tend to it. And, many women are working full time and aren’t home like they used to be. So, the tradition – which had been handed down through families – is being lost, and that’s why it’s important to keep it alive however we can,” she said.

Those who grew up with the bread long for that cheese-like flavor and fine crumbly texture. Those who aren’t as familiar often scrunch their noses up at the microbial bread’s distinct smell but fall in love at first bite.

This bread is much like our region – steeped in tradition and resourceful. It’s these qualities that help define Appalachia, and paying homage to these traditions helps keep our history alive.

The Appalachian bread is important in our state’s culinary history, and through devotees like Bardwell and Brown, this tradition will not be lost.

SALT RISING BREAD RECIPES

While Bardwell and Brown collected 150-200 salt rising bread recipes, most of them fell into two categories: the cornmeal & flour method or the potato method.

Both of the below recipes are featured in “Salt Rising Bread: Recipes and Heartfelt Stories of a Nearly Lost Appalachian Tradition” and were the ones the authors learned from.

Pearl Haines’s Salt Rising Bread Recipe

Ingredients:

1/2 cup scalded milk

3 teaspoons cornmeal

1 teaspoon flour

1/8 teaspoon baking soda

Preparation:

1. Pour milk onto dry ingredients and stir.

2. Keep warm overnight until foamy.

3. After the raisin’ has foamed and has a rotten cheese smell, in a medium-sized bowl add 2 cups of warm water to mixture, then enough flower (about 1½ cups) to make like a thin pancake batter. Stir and allow to rise again until it becomes foamy. This usually takes about 2 hours.

4. Next, add 1 cup of warm water for each loaf of bread you want to make, up to 6 loaves (e.g., 6 cups of water makes 6 loaves of bread). Add enough flour (20 cups for 6 loaves or about one 5 pound bag of flour plus 1/3 bag of flour). Form into loaves and grease tops. Let loaves rise in greased pans for 1.5 to 3 hours – sometimes longer if it is a cold day.

5. Bake at 350 degrees for 35 to 45 minutes or until loaves sound hollow when tapped.

Katheryn Rippetoe Erwin’s Salt Rising Bread

Ingredients:

1 medium Irish potato, sliced and placed in a jar

ADD: 1 tablespoon cornmeal

¼ teaspoon soda

¼ teaspoon salt

2 cups boiling water

Preparation:

1. Cover and let rise in a warm place until morning. (I set mine on top of the pilot light on my hot water tank). If the mixture is foamy and has the salt rising bread “aroma” the next morning, pour off the liquid and throw away the potatoes.

2. Mix 2 cups of very warm water with ½ cup of shortening. Then add 1 teaspoon salt, 4 teaspoons sugar, and 5 cups flour. Combine with rising mixture (starter) to make a stiff batter. Let this rise until double in bulk.

3. Work in 6 cups of flour, to make a soft dough. Divide into 3 portions. Let rise 10 minutes. Knead for 3 minutes. Place in 3 greased pans. Let rest until dough reaches the top of the pan.

4. Bake at 450 degrees for 15 minutes, then at 400 degrees for 25 minutes.

Food is so important because it’s over meals that memories are made, relationships are

formed and stories are shared.

It’s not just about the tasty morsels we devour; food is a piece of our culture.

You hear about a loved one’s day over the dinner table, learn a chef’s inspiration at a

restaurant, join in family traditions at a local small farm. These moments shape who we

– both as individuals and Appalachians – are.

Mike Costello, a West Virginia chef and co-owner of Lost Creek Farm with his wife Amy,

is exploring those foodways that help define West Virginia through storytelling dinners.

“Food is an incredible way to help tell a story. We create meals that in every way

possible are regionally inspired and rooted in tradition, rooted in place and tell stories

about people and their connection to place," Costello said. "Using food to indicate how

culture was formed here around the landscape and how Appalachians left their mark

are all part of a story that needs told."

What does that story look like? It could be anything from a braised rabbit dish crafted

with meat rabbits raised at the Lost Creek Farm to a grandmother’s recipe for cornbread

using an heirloom variety of corn. It could be sausage crafted in a traditional way from a

Spanish community in Harrison County or a dish adapted for the area based on the

availability of goods – like Italian dishes made without seafood.

Stories could take the form of local ingredients, heirloom varieties, traditional methods,

family recipes, or something else. What’s important is the meaning behind the food –

and that it reflects the culture, the landscape and the people.

"As long as Appalachia continues to get trendy, stories are gonna be told through food.

If we don’t take initiative and say this is our story to tell, someone will tell our story for

us,” he said.

Those stories are what separates local Appalachian cuisine from a trendy restaurant in

New York or Los Angeles simply using Appalachian ingredients stripped from context,

Costello said.

“Appalachian cuisine gets stereotyped as being one-note and monolithic, but there’s

more diversity reflected in our foodways than the outside narrative gives us credit for,”

Costello said. “But we’ve Lebanese populations in the Kanawha Valley, Spanish

communities in Harrison County, Serbian in the Northern Panhandle. The food culture

here has depth and complexity.”

Lost Creek Farm hosted a recent dinner at Rising Creek Bakery in Mt. Morris, Pa., that

featured buckwheat ravioli, salt-rising bread pudding and heirloom blue corn-crusted

trout filet. Each course was accompanied by a compelling story that gave diners a

sense of place and community.

Delicious food with an entertaining story, surrounded by people genuinely engaged in

learning about Appalachian food culture? That's my ideal meal.

And, the couple plans to expand their story concept at Lost Creek Farm.

"We have this vision to make the farm a real destination for food and culinary

exploration around food heritage by creating this food heritage incubator. It's designed

to foster this community around West Virginia food and stories around to West Virginia.

It's a space for people to share ideas and learn from each other and chefs can come in

and learn from home cooks who have been innovating in the kitchen around food and

food traditions, Costello said.

Costello is one of many spearheading this movement to reclaim the Appalachian food

narrative – one that takes pride in the authenticity of our place-based food. Through his

efforts and others, West Virginia is seeing some credit for our diverse, innovative

cuisine.

This initiative could turn this trend into a long-term respect and admiration for the

diverse culinary community in West Virginia. It's time others heard the story of West

Virginia.

Candace Nelson is a marketing professional living in Charleston, W.Va. In her

free time, Nelson blogs about Appalachian food culture at CandaceLately.com.

Find her on Twitter at @Candace07 or email CandaceRNelson@gmail.com.

Spruce and cider braised rabbit with chanterelle mushrooms

This recipe, from Mike Costello, uses meat rabbits raised at Lost Creek Farm. This was

something his grandpa’s family did in Braxton County in the early 1920s.

1 whole rabbit (3-5 lbs), either left whole or quartered.

2 medium yellow onions, coarsely chopped

1 cup Hawk Knob Appalachian Classic or other dry hard apple cider

1 cup rabbit stock (chicken stock can be substituted)

3 large cloves fresh garlic, halved

3 large cloves roasted garlic, halved

2 tablespoons salted butter

6 small (8 inch or less) spruce twigs, with needles plus 2 tablespoons lose needles

2 cups fresh chanterelle mushrooms, stem ends removed

1 tablespoon dry sherry

1 tablespoon salt, additional to taste

1 tablespoon sugar

1/2 teaspoon mustard powder

1/4 teaspoon black pepper, additional to taste

1/4 cup heavy cream (optional)

1/2 cup olive oil

Prepare the seasoning mix: Shred 1 tablespoon of lose spruce needles in clean

coffee/spice grinder, or chop finely. Combine with salt, sugar, mustard powder, black

pepper.

Brown rabbit: Pat rabbit dry, then coat with spice mix. In a medium to large cast iron

skillet or Dutch oven, heat a quarter inch of olive oil. Over medium heat, sear rabbit until

golden brown on each side, approximately 3-4 minutes per side. Remove rabbit from

skillet and set aside.

Prepare braising liquid: Add onions and fresh garlic to skillet, sauté over low to medium

heat until onions are slightly translucent. Combine onions and garlic with one cup of the

chanterelle mushrooms. Deglaze with apple cider, scraping bottom of pan. Add stock,

spruce twigs, roasted garlic and 2 tablespoons of butter. Bring to a low boil.

Braise rabbit: Set rabbit back in skillet and cover. Bake covered at 350 degrees for 45

minutes, or until rabbit is fork tender. Remove lid and bake uncovered for an additional

10 minutes. Return to stove top, heating over low heat, spooning braising liquid over

rabbit for several minutes, until rabbit develops a noticeable glaze.

Sauté chanterelles: While rabbit is braising, toss one cup chanterelle mushrooms with

olive oil and salt to taste. Sauté over medium high heat until mushrooms develop a rich,

golden brown color. Add dry sherry and cook until liquid is absorbed/evaporated.

Finish sauce: Remove spruce twigs and discard. Simmer braising liquid over medium

heat until sauce is slightly reduced and thickened to desired consistency. If desired, add

heavy cream, and reduce further.

Top with sautéed chanterelles. Serve over grits or mashed potatoes with fresh garden

vegetables.

The season for the wild Appalachian delicacy known as the morel mushroom has come to an end.

Typically found from March until May, depending on the weather, the Morchella ushers in the beginning of spring. I had been prolonging the season — unearthing my stash of dried morels and bringing them back to life with a little bit of water. But, alas, my last morel took its final journey to my tummy.

Worth it.

The wild edible found throughout our West Virginia hills has seen some interest from chefs in large cities — driving up demand and resulting online sales at about $65 per 4 ounces, according to one site.

While they’re now trendy, morel mushrooms have roots in our culinary culture. Mountain people hunt, fish and forage for berries and, of course, mushrooms, creating that strong connection between the land and our people.

ADVERTISING

As a child, I would accompany my grandma through the woods behind her house in search of the elusive morel mushroom, or as my grandma says, “merkels.”

You’ve probably heard morels, “molly moochers” or “hickory chickens,” but in my part of Appalachia, it was always merkels.

Folklore says a mountain family was saved from starvation by eating morels, and thus they were called miracles — or merkels in a strong Appalachian dialect. Some also say the scientific name for Morchella is thought to have derived from “morchel,” an old German word for mushroom, which could have been a source for name merkel.

Whatever the name, these mushrooms became a fixture of my youth in West Virginia.

We would hunt merkels for hours.

“Find the ones that look like a honeycomb,” my grandma would tell me. “Not the smooth ones, those are poisonous.”

In her kitchen, merkels could often be found strung up with fishing line. A small prick from her sewing machine needle in the stem of the mushroom, a quick loop with the line and you can enjoy merkels long into the winter months, if you possess any shred of self-restraint.

Nowadays, my pizza is always topped with mushrooms, and lasagna isn’t lasagna without that touch of umami. Maybe that’s because the love of the mushroom was instilled in me at a young age.

My grandma, now 75, forages less frequently these days. But, along with the love of merkels, she instilled in me pride in our state.

West Virginia is a beautiful place, and while others may take for granted all the incredible — and delicious — gifts it bears, my grandma never did. While she enjoyed hunting merkels, she more so enjoyed being in nature where she could appreciate the birds, the rolling hills and the beautiful flowers. The bounty was a bonus.

And, while my morels may have been the last of the season, you can still get in touch with your foraging roots with chanterelles, chicken of the woods and others as they begin popping up in the upcoming seasons.

Whether to you it’s a morel or a merkel — or something else — I’m not sure a mushroom from any other place would be as tasty.

Candace Nelson is a marketing and public relations professional living in Morgantown. She’s also the author of

“The West Virginia Pepperoni Roll,” a comprehensive history of the unofficial state food, and blogs about West Virginia food culture at CandaceLately.com. Follow @Candace07 on Twitter or email Candace127@gmail.com.

Dorothy’s Fried Merkels

This is the recipe my grandmother made for me as a child. As is the case whenever I ask her for precise measurements, most of the cooking is done by eyeballing the amounts. The following is not fancy, but it’s real. It’s how I grew up eating merkles, and I hope you enjoy.

1 egg

1 cup of flour

mess of morel mushrooms

canola oil

Rinse the morels in cold water to remove loose dirt and insects.

Crack an egg.

Slice the mess of morel mushrooms.

Coat the mushrooms in the egg.

Put the mushrooms in a plastic bag full of flour to coat them.

Pour about 2 inches of canola oil in a skillet and deep-fry it until the mushrooms become crispy, like french fries.

Top with salt and pepper.

Share the bounty with your friends, but if you plan to return again, never tell them where your morels were hiding.

All work property of Candace Nelson. Powered by Blogger.