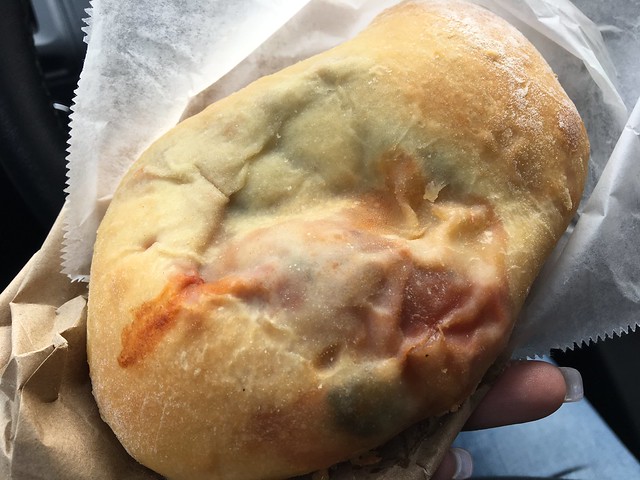

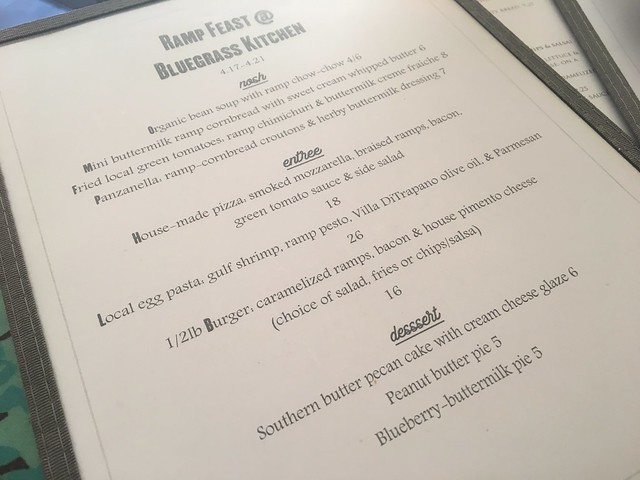

One of the hallmarks of Spring in West Virginia is ramps. Ramp feeds, ramp festivals, ramparoni rolls. And recently, Bluegrass Kitchen hosted their "Ramp Feast."

One of the hallmarks of Spring in West Virginia is ramps. Ramp feeds, ramp festivals, ramparoni rolls. And recently, Bluegrass Kitchen hosted their "Ramp Feast."

Fried green tomatoes with ramp chimichurri.

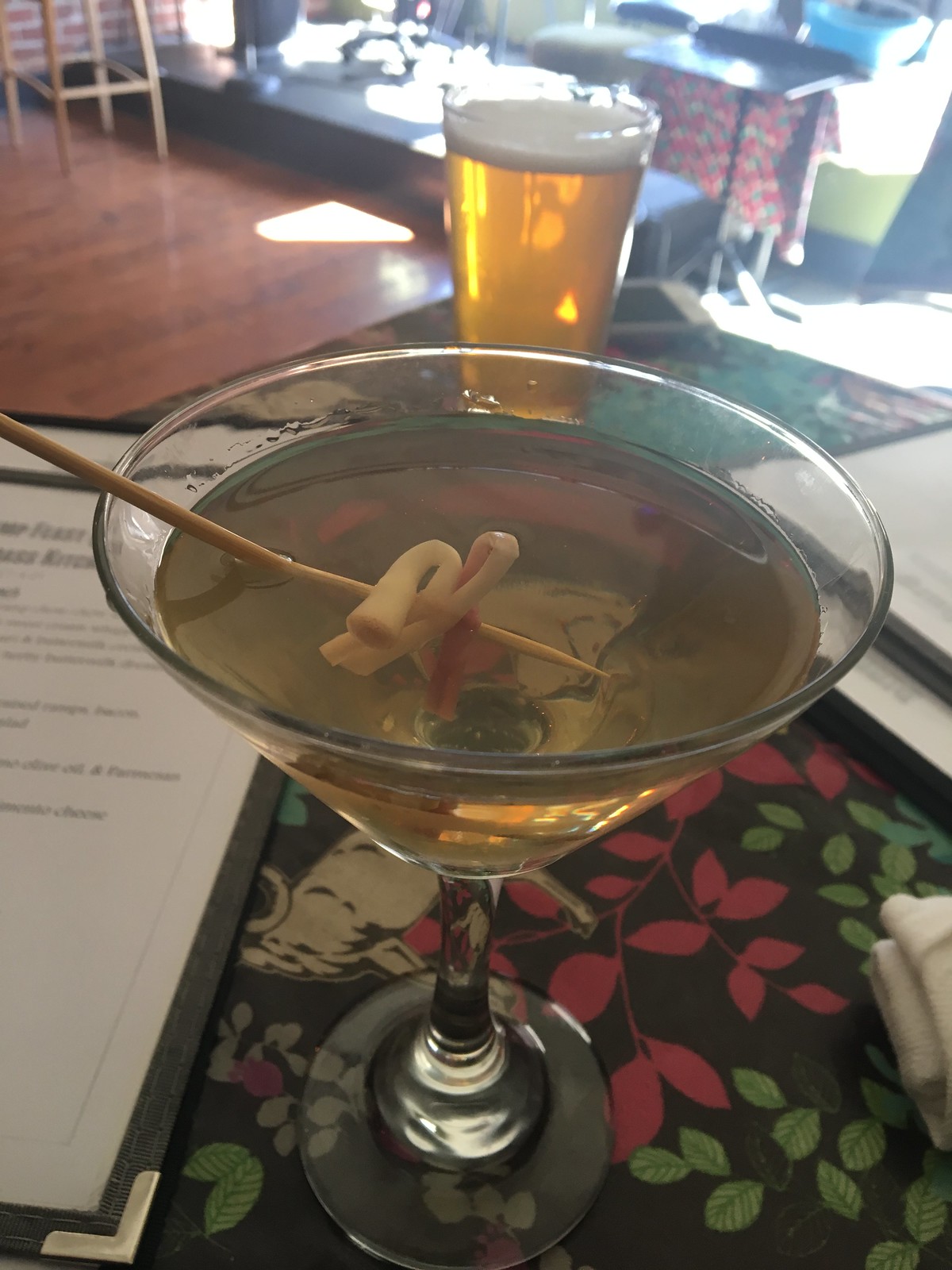

And - a ramp martini! Have you ever tried one?

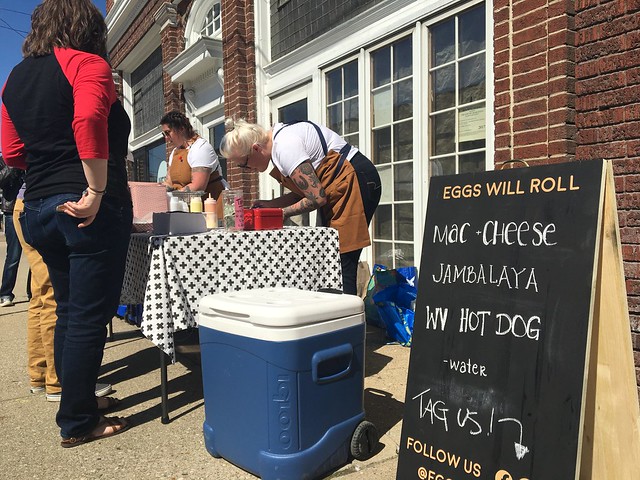

My super talented friend Kayla has launched her 10-year dream of owning an eggroll food truck. The truck part is a coming soon, and to get there, the business is up doing pop-up shops around Charleston with some of the most unique egg rolls you'll find anywhere!

My super talented friend Kayla has launched her 10-year dream of owning an eggroll food truck. The truck part is a coming soon, and to get there, the business is up doing pop-up shops around Charleston with some of the most unique egg rolls you'll find anywhere!

Eggs Will Roll was born from this party. And, they've added new eggrolls, too - including a West Virginia hot dog one with hot dogs, tater tots, cole slaw, onions and chili with a mustard aioli sauce.

At Kinship Goods in April, they had a mac & cheese, jambalaya and West Virginia hot dog. And, they'll be doing lots more events coming up soon!

West Virginia hot dog, macaroni & cheese and jambalaya. Have you tried them?

Follow Eggs Will Roll on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram under @EggsWillRoll.

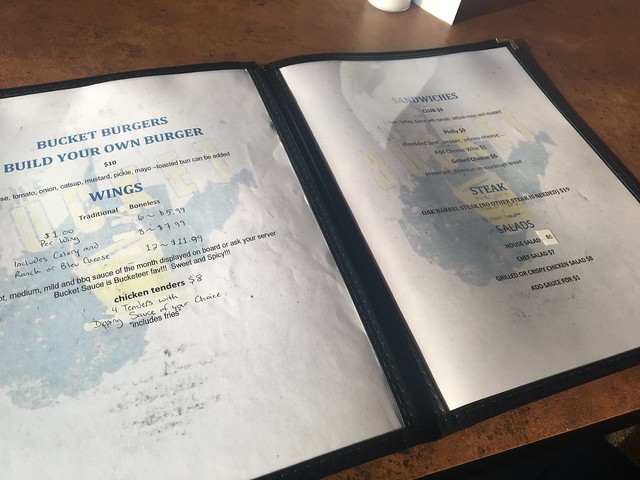

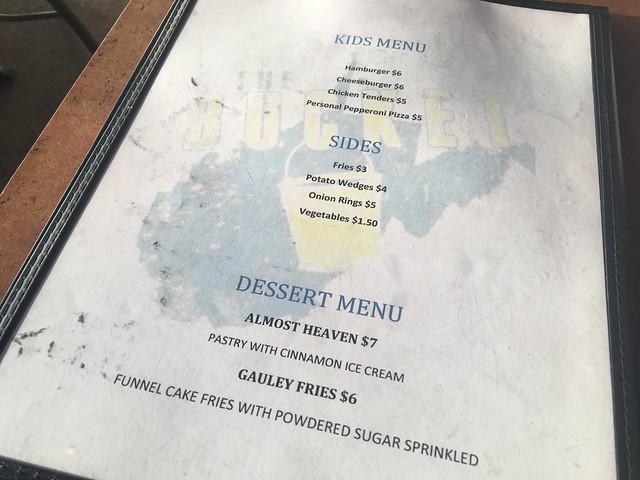

When looking for a new place to get some grub, Dunbar's The Bucket stood out to me because, wait for it: deep. fried. pepperoni. rolls. That was a quick way for it to rise to the top of our list.

Dawn and I headed here (after a bit of traffic), and were delighted with the large, wall-wide windows that let tons of beautiful light in. There is a stage and lots of tables in the center.

The menu in person is fairly small, but there are actually a lot more options online - including the deep-fried pepperoni rolls.

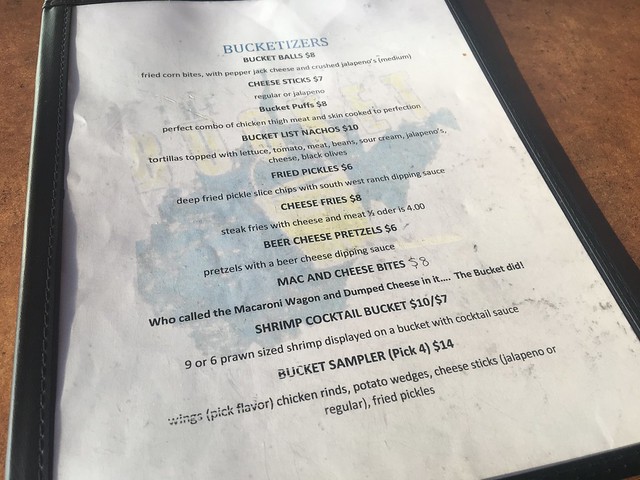

But there is a lot of fun appetizers - mac & cheese bites, nachos, fried pickles, etc.

“The Bucket” was formed in 2017 to be a place where anyone could visit and enjoy a little West Virginia hospitality, some good entertainment, tasty food and a great atmosphere! You should expect to enjoy the patio area in the summertime and the outside bar area as well in the winter. The inside has a fantastic and modern LED backlit bar top with color change and an amazing cold selection of cold beer and local brews “we have the coldest around”. We invite you to come and sit for a spell and have some great food, cold drinks and live music. You want family friendly? The bucket is family friendly, bring the kids and watch the game….. We don’t turn the kids away until after 9 on Friday and Saturday (cause the adults have to have a little fun time occasionally). If you want to know where its happening at “its at the bucket” 4030 Washington St. West Dunbar WV 25312. Yall come and enjoy!!! (ABOUT)

Deep-fried pepperoni rolls served with marinara

Soft pretzels with beer cheese

Cheese fries

Boneless wings in "Bucket Sauce" - which is a sweet and spicy sauce.

Have you been?

One of my most recent columns for the Charleston Gazette-Mail was about deviled eggs:

It’s not a celebration in my house without the tangy, sweet addition of deviled eggs to the dinner table.

Deviled eggs — the tastier version of hard-boiled eggs that involves scooping out the yolk and mixing it with mayonnaise and mustard — serve as appetizers for every holiday meal, family event and significant milestone in the Nelson household. And, it appears I’m not alone.

In Mark Sohn’s book “Appalachian Home Cooking: History, Culture, and Recipes,” he noted a list of the most common Appalachian foods: soup beans, apple stack cake, biscuits and gravy, and other iconic staples.

A little further down the list: deviled eggs.

“No mountain dinner is complete without deviled eggs. At dinner on the grounds, they may be plucked away before the blessing is given, and at Thanksgiving dinners, even small families often serve two platters. Local markets sell deviled egg trays, and unlike yeast dinner rolls, which few cooks prepare at home, many cooks make deviled eggs,” he wrote.

These little bites, dressed in bright yellow and bold red, awaken the taste buds: salty, a little sweet, but mostly tangy, and certainly satisfying. That’s in part how they got their name.

As a culinary term, “devil” is most often used to describe dishes with spicy, tangy, hot or fried foods, first appearing in Great Britain in 1786, according to A&E’s History Channel. By 1800, “deviling” became a common verb that was used describe making food spicy or hot.

But the concept of boiling eggs, topping them with spicy sauces and serving them while entertaining goes back even further — to ancient Rome. They were seasoned with oil, wine, honey, vinegar or broth. In the 13th century, stuffing the eggs with cilantro, onion and coriander became popular in what is now Spain. By the 15th century, stuffed eggs had taken over Europe, where they were filled with raisins, cheese and herbs.

Our beloved “deviled egg” — sometimes called a “dressed egg,” made with mayonnaise (or in my household, Miracle Whip), mustard and paprika — became popular in Appalachia in the 1940s. Back then, measuring spoons weren’t big in my family — or many others in West Virginia — so our recipe for deviled eggs calls for a “smidgen” of this and a “bit” of that.

That leads to the following exercise: Mom boils the eggs and makes a yolk mixture and hands spoons to my father and me to try it.

“Too sweet,” he says. “Yeah, add more vinegar!” I say. We repeat this process approximately four or five times. It might be because we like eating the yolk mixture, or maybe it’s because we like tangier foods as we get older, but we never grant approval after just one round. And I have a sneaking suspicion this is intentional on my mother’s part, because she enjoys the tradition, too.

This simple amuse-bouche has been a staple at every major meal, even when the main course changes. Turkey for Thanksgiving? Still snacking on deviled eggs for lunch. Ham at Easter? Only if we have deviled eggs for breakfast. Potluck for family reunions? If there aren’t deviled eggs, the reunion is canceled.

And deviled eggs aren’t unique to my household or Appalachia — you can find them at high-end restaurants in big cities topped with unique ingredients — but they sure do play a role in our food culture. While other places may include them as an option, here, they’re a requirement.

So, tell me, how do you make your deviled eggs? My recipe is simple but tasty. What makes yours unique?

It’s not a celebration in my house without the tangy, sweet addition of deviled eggs to the dinner table.

Deviled eggs — the tastier version of hard-boiled eggs that involves scooping out the yolk and mixing it with mayonnaise and mustard — serve as appetizers for every holiday meal, family event and significant milestone in the Nelson household. And, it appears I’m not alone.

In Mark Sohn’s book “Appalachian Home Cooking: History, Culture, and Recipes,” he noted a list of the most common Appalachian foods: soup beans, apple stack cake, biscuits and gravy, and other iconic staples.

A little further down the list: deviled eggs.

“No mountain dinner is complete without deviled eggs. At dinner on the grounds, they may be plucked away before the blessing is given, and at Thanksgiving dinners, even small families often serve two platters. Local markets sell deviled egg trays, and unlike yeast dinner rolls, which few cooks prepare at home, many cooks make deviled eggs,” he wrote.

These little bites, dressed in bright yellow and bold red, awaken the taste buds: salty, a little sweet, but mostly tangy, and certainly satisfying. That’s in part how they got their name.

As a culinary term, “devil” is most often used to describe dishes with spicy, tangy, hot or fried foods, first appearing in Great Britain in 1786, according to A&E’s History Channel. By 1800, “deviling” became a common verb that was used describe making food spicy or hot.

But the concept of boiling eggs, topping them with spicy sauces and serving them while entertaining goes back even further — to ancient Rome. They were seasoned with oil, wine, honey, vinegar or broth. In the 13th century, stuffing the eggs with cilantro, onion and coriander became popular in what is now Spain. By the 15th century, stuffed eggs had taken over Europe, where they were filled with raisins, cheese and herbs.

Our beloved “deviled egg” — sometimes called a “dressed egg,” made with mayonnaise (or in my household, Miracle Whip), mustard and paprika — became popular in Appalachia in the 1940s. Back then, measuring spoons weren’t big in my family — or many others in West Virginia — so our recipe for deviled eggs calls for a “smidgen” of this and a “bit” of that.

That leads to the following exercise: Mom boils the eggs and makes a yolk mixture and hands spoons to my father and me to try it.

“Too sweet,” he says. “Yeah, add more vinegar!” I say. We repeat this process approximately four or five times. It might be because we like eating the yolk mixture, or maybe it’s because we like tangier foods as we get older, but we never grant approval after just one round. And I have a sneaking suspicion this is intentional on my mother’s part, because she enjoys the tradition, too.

This simple amuse-bouche has been a staple at every major meal, even when the main course changes. Turkey for Thanksgiving? Still snacking on deviled eggs for lunch. Ham at Easter? Only if we have deviled eggs for breakfast. Potluck for family reunions? If there aren’t deviled eggs, the reunion is canceled.

And deviled eggs aren’t unique to my household or Appalachia — you can find them at high-end restaurants in big cities topped with unique ingredients — but they sure do play a role in our food culture. While other places may include them as an option, here, they’re a requirement.

So, tell me, how do you make your deviled eggs? My recipe is simple but tasty. What makes yours unique?

All work property of Candace Nelson. Powered by Blogger.